Jouni Harala

JOURNAL

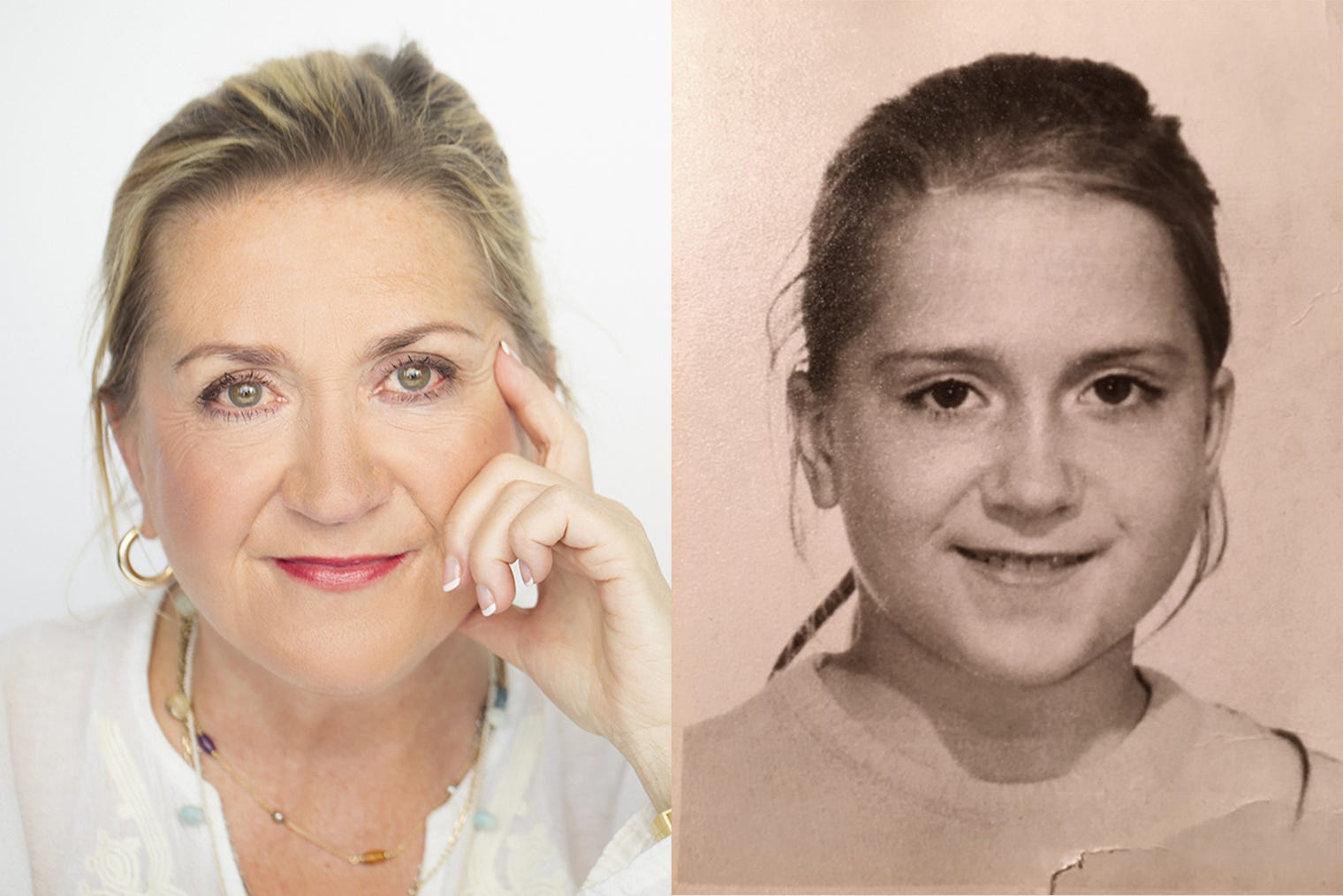

A Letter to My Younger Self

I was born and raised in Kallio, a traditional working-class district of Helsinki. Growing up, I learned a certain street smartness that has profited me greatly in my work as an author and a therapist.

Kallio was a rough neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s; I have often compared its street life back then to Amarcord, a movie by Federico Fellini. When I was born, our family lived next to the local library. Everyone in our slightly peculiar family loved reading, and the library became a second home to me—a home much quieter and safer than my family’s. I knew early on that I wanted to write books.

MY PARENTS FIRST MET in Vyborg, and my sister was one of the last babies born there before its evacuation in June 1944, amid the chaos of air raids. Since an early age, I have been familiar with a cross-generational feeling of sadness and loss. I’m a second-generation immigrant—I have inherited a feeling of restlessness and rootlessness, but also a certain adaptability, a cosmopolitan worldview, and survival strategies.

As a young man, my father was wounded in the leg in the Winter War. I’m the daughter of a limping man. He became an alcoholic over the years; the war was eroding his mind, along with the minds of an entire generation. Our whole family suffered from his alcoholism: my mother was sickly, and my sister’s life was overshadowed by her untreated cleft palate and rheumatism.

Our little apartment was located near a Salvation Army night shelter, a prison, the local jail, and a boys’ home run by the local chapter of the settlement movement. That was where I learned to dream. I wanted to escape from the narrow alleys and confined courtyards and the dimness of the tiny apartments into bright light and space, a world of the arts and adventure.

I WAS BORN LONG AFTER my sister, when my parents were already older. I was shy and wild at the same time, with a vivid imagination. My nickname as a child was Patent, because I came up with all kinds of tricks and gimmicks and new games all the time. The world of books and the arts was also very important to me. I took up classical ballet, loved drawing, and was good at sports: sprinting and skating. I dreamed of an island of my own.

I started writing poems at the age of seven or eight, in addition to keeping a journal. My journals had names, and the entries resembled letters: “Dear Anne, here’s what happened to me today.” I also wrote letters to famous figures—Audrey Hepburn, Danny Kaye, and Donald Duck, for example—that I never sent.

My father was a fire insurance clerk who worried about work while at home. He was an illegitimate child raised by his grandparents, and he never really knew his father or mother. My mother was a stay-at-home mom who had been forced to abandon her dreams of a career because of the war. Before meeting my father, she had given birth to a baby girl—this I didn’t discover until after my mother’s death.

The air in our home was heavy with secrets and dreams that had yielded to reality. There was a great deal of talk about Karelia, the region my parents hailed from and that Finland had to cede to the Soviet Union after the war.

My father was violent when drunk, and we sometimes had to escape into the night to avoid his rage. From my earliest years, books and writing were my escapes from a reality that was dreary and even scary at times.

I WAS AN EXTREMELY SHY child and terrified of starting school. The local school was a huge building, with long, echoing corridors. It looked like a prison to me.

I was a loner, onlooker, and observer throughout my school years. I would have liked to join the others, but I didn’t know how. I couldn’t find the right words. I was ashamed of my poor and peculiar family and my father’s drinking, and even of my mother and sister. At the same time, I wrote elaborate adventure stories at home, in the vein of the Famous Five series by Enid Blyton.

I was an invisible child, willingly and unwillingly, but fortunately I had a few good friends, who were important to me. We wrote letters to one another, even though we saw each other daily at school. In our letters, we shared secrets—secrets that we didn’t have the courage to share face-to-face.

I DIDN’T LIKE COMPETITIONS back then, and I still don’t. Not until I went to university did I become more open, thanks largely to my first boyfriend, who supported me, tolerated my peculiarities, and believed in my talent. I studied several subjects at the University of Helsinki. I was interested in everything and majored in domestic literature, applied psychology, and English philology.

It took me seven years to complete a bachelor’s degree, and it took me just as long to write my debut novel, Sonia O. Was Here. It was an exhausting undertaking, and nothing was certain after I had completed the final version of the manuscript. My biggest wish was for my book to be published. And of course I wanted to leave my mark in the world of Finnish literature.

In the columns I had written for cultural and student magazines, I had pretty much given the finger to the strongly politicized cultural circles of the 1970s and the fossilized literary canons controlled by men. With philosopher Esa Saarinen, I had also challenged the “old farts” at a prestigious literary society in the fall of 1980, a year before my debut novel came out. In other words, by no means did I make my literary debut easy for myself.

I was defiant back then, but at the same time shy and self-critical. I was still aware of my modest background. In the cultural circles, everyone seemed to be from a better and somehow famous family.

A bold book written by a young woman about growing into womanhood and sexuality attracted immense attention. In addition to publicity, I had to deal with the story of the book being associated with me personally, which was a confusing experience, even though I had known to expect something to that effect. However, Sonia O. Was Here was not autofiction—it was a very deliberate response to all the odysseys of young men, to literature as a form of male narcissism.

MY LIFE CHANGED after the publication of my first novel, but not completely. Life became more secure: I took out a mortgage and bought my first home, in an apartment building in the neighborhood where I had grown up. My mother was more seriously ill at the time, so I visited her almost daily to manage her and my sister’s daily lives—they lived together until my mother’s death. Amid that circus of celebrity and chores, I realized how important it was to hold on to my own routines.

When I think back on myself as a debut author, I still feel great joy and pride. My childhood dream came true, and my feelings of loneliness, alienation, and even suffering had new meaning. The shy and serious young woman hit the jackpot after all. Many wouldn’t have believed it. At the university, there were many literary students who made a great deal of noise about aspiring to become authors. In writers’ groups and circles, there was often tough competition under the surface: which one of us will become a famous author?

When I think back to the start of my career, I also think of the years and decades that followed. Dozens of novels, collections of poems, screenplays, works of nonfiction, translations, journalism, reportages, columns, work on television and on the radio, work as a media specialist. Colorful networks of people, trial and error, setbacks, disappointments and grief—but also joy, love, infatuation, friendship, travel, two marriages, two daughters, cats, dogs, Greece, and India.

Eventually, also work as a general and sex therapist—work in which the importance of insightful listening and the power of dreams are present and true every day.

IN 2011, HAVING SEEN an advertisement at the university about a four-year program in solution-focused psychotherapy, I made an intuitive decision to apply. I graduated as a therapist in 2015. In 2018, I graduated as a sex therapist from a program of the Family Federation of Finland.

I have now worked as a therapist at a psychotherapy center for four years, and I also work as the personnel manager of one of its units. I have proved to myself that many issues—fear, shame, loneliness, and insecurity—can be turned into resources.

During a lecture a few years ago, I realized that I was a highly sensitive person, and many pieces fell into place in my life. I also realized I was born with this neurological trait, regardless of the dynamics of my childhood family. That was a relief; I no longer needed to search for reasons.

Today, around one-third of my clients are highly sensitive, and I also studied the topic for my thesis at the university and for my diploma work for the training program in sex therapy. On top of that, I wrote a novel, My Life as a Deer, about the discovery that I am a highly sensitive person. I have received ample feedback on the book—beautiful and touching letters and messages.

I WOULD VERY MUCH LIKE to talk with my younger self about being highly sensitive. That young girl and woman was so scared, always retreating and escaping.

So often, she had no self-confidence or self-esteem. Now I recognize in her many characteristics of being a highly sensitive person: strong intuition, a longing for aesthetics, a hunger for intense relationships, rapidly changing moods, a need to spend time alone, an appreciation of nature and silence.

As a therapist, I feel great joy when I can help young men and women—who often come to see me because of loneliness, anxiety, and problems with relationships—to become aware of this trait. Gradually, they learn to be proud of what they used to be ashamed of and see sensitivity as a resource and strength.

This is where young Anja is leading me by the hand. She would be proud of me; I’m finally proud of her.

By Anja Snellman

Published with permission from Docendo